Since its founding in 1865, The Nation has published some of the most important voices in American poetry, including Hart Crane, Elizabeth Bishop, Amiri Baraka and Adrienne Rich.

But last week, the venerable progressive weekly published what may have been a first: an apology for one of its offerings that ran twice as long as the poem itself.

The 14-line poem, by a young poet named Anders Carlson-Wee, was posted on the magazine’s website on July 5. Called “How-To,” and seemingly written in the voice of a homeless person begging for handouts, it offered advice on how to play on the moral self-regard of passers-by by playing up, or even inventing, hardship.

But after a firestorm of criticism on social media over a white poet’s attempt at black vernacular, as well as a line in which the speaker makes reference to being “crippled,” the magazine said it had made a “serious mistake” in publishing it.

“We are sorry for the pain we have caused to the many communities affected by this poem,” the magazine’s poetry editors, Stephanie Burt and Carmen Giménez Smith, wrote in a statement posted on Twitter last week, which was posted above the poem on the magazine’s website a day later, along with an editor’s note calling the poem’s language “disparaging and ableist.”

“When we read the poem we took it as a profane, over-the-top attack on the ways in which member of many groups are asked, or required, to perform the work of marginalization,” they wrote. But “we can no longer read the poem in that way.”

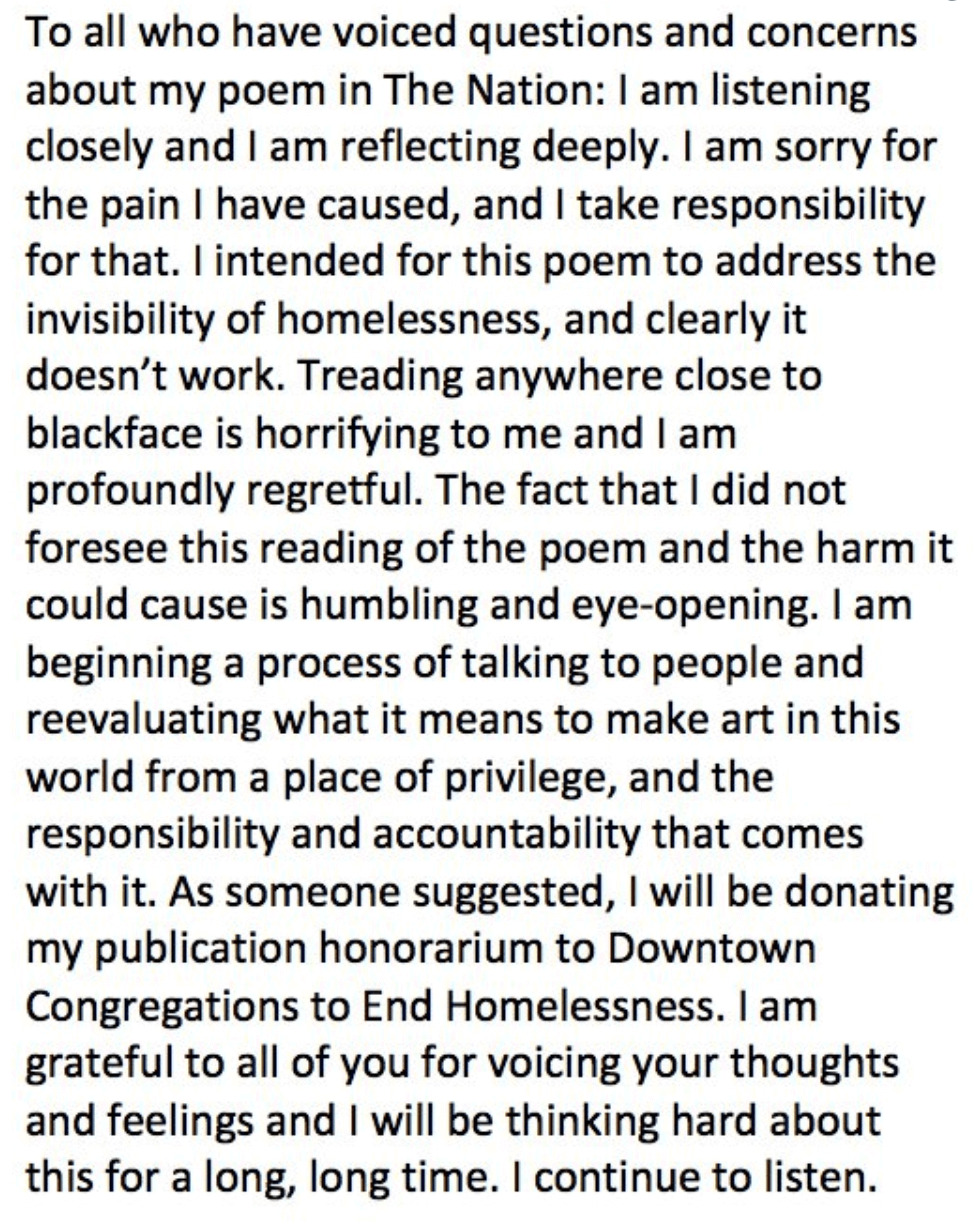

Mr. Carlson-Wee also posted his own apology. “Treading anywhere close to blackface is horrifying to me, and I am profoundly regretful,” he said in a statement posted on Facebook and Twitter.

For an art form starved for attention, it was not the kind of publicity poetry needed. To the mostly right-leaning media outlets who covered the controversy, it was just the latest skirmish in the broader battle over cultural appropriation and political correctness.

That debate shows no signs of abating. Earlier this month, after intense criticism, a theater in Montreal cut short the run of a production by the director Robert Lepage that featured mostly white actors playing black slaves. A week later, the actress Scarlett Johansson withdrew from playing a transgender role after an online outcry.

The Nation did not remove or alter the poem. But its handling of the incident provoked criticism even from within its ranks for the way it broke with the magazine’s traditional way of handling controversy: by publishing critical letters, not by ducking for cover from Twitter storms.

“I can’t believe @thenation’s poetry editors published that craven apology for a poem they thought was good enough to publish,” Katha Pollitt, a columnist for the magazine and herself a poet, said on Twitter on Tuesday. The apology, she wrote, “looks like a letter from re-education camp.”

Online battles over cultural appropriation may be relatively new, but Mr. Carlson-Wee’s poem is part of a long, queasy history of white poets adopting black vernacular.

Some of that work remains important, if cringe-making, like the portions of John Berryman’s magnum opus, “The Dream Songs,” written in the 1960s, that adopt a “blackface” persona. Other work has aged even less well, like Vachel Lindsay’s “The Congo,” first published in 1912, which includes lines like “‘BLOOD’ screamed the skull-faced, lean witch-doctors.” (A recitation of parts of the poem was included in the 1989 film “Dead Poets Society,”complete with exuberant jungle whoops.)

On: “A POEM IN THE NATION SPURS A BACKLASH AND AN APOLOGY”. Inflammatory attacks on publishers and writers for honest attempts at social progress and dialog is a mistake on many levels. It silences voices whose intentions and directions have ethical integrity, despite vocal, even strident, protests from those who hold different and/or opposing views. These attacks narrow the platform for dialog, for mutual understanding, and for constructive evolution of socio-politcal and socio-culrural writing/expression. There are no “experts” in the world of writing, only opinions, with vastly different experiences, different sensibilities, and different priorities. There is no question that some opinions hold more water than others, but dogmatic, emotional condemnations of well-intentioned writers don’t do service to the arts of genuine expression or to journalism.