EMPEROR MING MEETS AUNTIE DEE ARNOLD JOHNSTON

In late November, 1951 my pal, Jim Simpson and I were standing outside our tenement building at Farme Cross in Rutherglen. I was a week or so away from leaving Scotland with my parents, Jimmy and Bessie Johnston, so Jim and I were settling important questions.

“D’ye think there’s any such thing as television?” Jim said; “Maybe in London?”

“If there is, I’ve never heard o’ it.” I desperately wanted it to be true, but I was playing the skeptic; “I mean, I’ve heard o’ television, but only as an idea.”

“But there’s Flash Gordon,” Jim argued; “Emperor Ming an’ Doctor Zarkov are aye on yon big screens.”

Jim and I had watched the Flash Gordon film serial with Buster Crabbe at different theatres, Jim at the Greens just off Rutherglen’s Main Street and I at the Empire, located on Cambuslang’s Main Street near the tram-car terminus, often referred to by local wags as, “the tar carminus.”

In any case, we’d noted in our separate observations of Flash Gordon that the evil emperor Ming the Merciless—as played with villainous gusto by Charles Middleton—could transmit live pronouncements and threats to the entire planet Mongo on a huge triangular screen. But it all seemed like Hollywood magic, like the cheesy spaceships that wobbled across the skies of Mongo, obviously suspended on strings you could almost see. Jim and I concluded that television was a pleasant fantasy for a hazy future.

“If it’s comin’,” I said, “it’s no’ comin’ for a long time.”

Not long after this conversation my parents and I set off for the United States. Since the end of World War II—when my father was demobilized from Britain’s Territorial Army—we’d been living in Rutherglen, my father’s hometown just east of Glasgow, about three miles west of my mother’s former home in Cambuslang where I’d been born in the parlor of my grandparents’ tenement.

In early December we took a big black taxi to the cavernous Glasgow Central railway station where we caught a train to the south of England. The train was crowded, and I wound up standing for the entire fourteen-hour journey amid clouds of cigarette smoke that dissipated only slightly when someone would yank the leather strap on a window to let in some fresh cold air, as well as smoke from the train’s coal-fired engine.

In Southampton we jostled up the Queen Elizabeth I’s gangway among a horde of other passengers for the week-long voyage to New York. As we stood on the deck waiting to be directed to our compartments, the great liner’s foghorn went off, sounding like the Trump of Doom—or maybe like all of Joshua’s trumpets bringing down the walls of Jericho—and making my entire body vibrate like a tuning fork. The noise couldn’t have made clearer to me that life from now on would be full of shocks.

My great-aun,t Matilda Findlay and her family had immigrated to the States in the 1920s, along with my mother’s oldest sister, Frances Arnold. By the time we set off on our journey, the Findlays were well-established in Detroit, Michigan, where Aunt Tillie lived in a modest East Side bungalow with her daughters Anne and the recently-divorced Francie and her children Roy and Maureen.

Two other Findlay sisters lived in their own East Side homes, Agnes with her husband Joe Critchlow and daughter Cindy, who was a little younger than I, and Mary with her husband, Hank Hayes. Joe Critchlow was a Canadian who had met Agnes when the Findlays were vacationing in Leamington, Ontario, in the cottage Aunt Tillie had bought for $800, and which the family still owns. Joe’s identical twin brother, Tony worked in the Heinz plant in Leamington. I’d actually encountered Joe during the war, while I was still a toddler and he was on leave from his duties with the Royal Canadian Army. He’d left me as a gift of an aluminum casting of an automatic pistol, the heft and smooth brushed surface of which I can still feel in my hand. Mary’s tall Oklahoma-born husband, Hank owned an appliance store on Detroit’s Mack Avenue only a few blocks from Aunt Tillie’s house.

My Aunt Fannie was now happily married to Milan Mitchell, a former displaced person from Lithuania whom she’d met at the Chrysler plant where they both worked, he as a foreman and she on the assembly line. I was to learn over the years that she and Mitch, as everyone called him, were almost a textbook illustration of the American Dream. They lived in a small, immaculate house on Lappin Avenue, where Mitch lovingly tended the flower-bordered bent-grass lawns in the front and back yards. Their basement parties were always memorable, the walls decorated with cutouts of risqué Vargas pinups, the beams festooned with colored crepe ribbons, the bar stocked with exotic liquors and liqueurs, and whimsical ornaments everywhere, like the grass-skirted wooden hula dancer with red lightbulb nipples. Fannie and Mitch were childless, but they loved to indulge their nephews and nieces whenever possible. Later in the 50s, when I saw Rosalind Russell in Auntie Mame, I realized that I’d had my own Auntie Mame all along. And like the men in Mame Dennis’s life, my Uncle Mitch watched and admired Fannie with quiet pleasure.

For years our entire family in Detroit had been encouraging my parents to come to America, the land of opportunity. And finally, amid Britain’s postwar austerity, chafing in a dirty, demanding, and dangerous job at the Empire Aluminium Works, my father decided the time was right. My mother was less sanguine about leaving Scotland. I, of course, was nine and had no say in the matter, even though I’d miss my friends in Cambuslang and my schoolmates at MacDonald School in Rutherglen, which my father had attended before me.

For weeks before we left home my parents had been selling or giving away possessions we couldn’t take with us and packing the stuff they needed to set up a life in a new place. The items I remember most vividly were more ornamental than utilitarian: a brass-covered wooden box embossed with a seascape featuring Spanish galleons; a brass wall plate with a similar motif; a chiming wooden Big Ben clock, a wedding gift to my parents from my mother’s South African cousin; a Royal Doulton figurine of an eighteenth-century lady; and a cartoonish plaster dwarf in the Disney mode that we called “Gloopy.” I still have the brass box, the plaque, and the clock, which chimes on the quarter hour every day.

I, too, gave away quite a few of what my wife Debby calls PBMs—Precious Boyhood Mementos. The few things I kept included small plastic figures—a brown cocker spaniel, a white dachshund, and two motorcycle policemen (one brown and one pink)—two Dinky automobiles (a Rolls Royce and an Armstrong-Siddeley), Dinky versions of the Queen Mary and (synchronously) the Queen Elizabeth, and a small plastic clown’s head with a lever on the back that made his nose grow and his tongue stick out. I also took a few books: Treasure Island, Kidnapped, The Swiss Family Robinson, The Coral Island, and Pilgrim’s Progress, the latter an uplifting gift from Miss Henry, the gentle and soft-spoken spinster who lived in the flat above us. Most of the toys nestle in a plastic bag in my file cabinet, and I still have the books, too.

Another prized possession that went with me was a specially-minted and boxed five-shilling piece—a crown—commemorating the 1951 Festival of Britain. I’d received it a few days before we left Scotland from my grandmother’s tailor, Mr.Campbell, a small, impeccably-groomed (and tailored) man with iron-gray hair and a trim pencil-thin moustache. His shop was in Glasgow, but he traveled to surrounding towns soliciting bespoke business, and like most people who met her had a soft spot in his heart for my Granny Arnold. As I see now on Ebay and elsewhere, lots of the coins are still around, but I was touched by Mr. Campbell’s gesture and continue to number mine among my PBMs.

I’d said my goodbyes to red-haired David Dennistoun, a friend from my grandmother’s Somervell Street tenement in Cambuslang, and to Jim Simpson and my other chums from MacDonald School and the Farme Cross neighborhood—John Belshaw, Michael Donatello, George Conkie, and my best friend Andrew Guy. I’d even tried giving a little amethyst ring I’d won at a carnival to a girl from my MacDonald class—Ann Clark. No such luck. But the irony of unrequited love struck me again a few days later from an unexpected angle. Another girl from my class, Rena McCurdie, about whom I’d noticed only her Dutch-boy bob and outsized hair ribbon, chased me all around Farme Cross in a vain attempt to give me a goodbye kiss.

A last MacDonald School irony was the letter of recommendation my parents secured for me from the Assistant Headmaster, Mr. Hamilton (“Hammy” to us pupils), a tall stern man with a pointy red nose. The letter described me as “a very intelligent boy” and was primarily responsible for my being placed among students a year older than I at Detroit’s Hosmer Elementary School. The irony was that my only real contact with Mr. Hamilton had been one morning almost a year earlier when my class had been lined up with all the others, ready to enter the school as we did every day to recorded Sousa marches. Someone—sneaky little Sandy Pettigrew, I think—poked me from behind, and when I turned and uttered a protest Mr. Hamilton decided to make an example of my disorderly conduct.

Mr. Hamilton led me to his class—the most senior in the school—and before this collection of strangers punished me in a particularly humiliating way. Back then teachers in Scotland still used corporal punishment in the form of the taws, a thick leather strap divided in three at the business end. The custom was to have the offending student hold out a hand and take a lengthwise stroke on the palm. On this morning, though, Mr. Hamilton made me hold out both hands, one under the other to assure maximum impact on the top palm. I’d been punished by “the strap” as we students called it, but never like this. And it really hurt because Mr. Hamilton was able to make the triple ends of the strap strike not only the palm, but the tender wrist just beyond. He did this three times, finally making me cry, which I’d never done before my own classmates. I returned to my class, Miss Kidd’s, with my hand red and throbbing with pain, my eyes tear-stained, both shamed and puzzled at the ferocity of the punishment.

When I returned home that day, my hands and wrists still bearing the marks of the strap, I had to dissuade my father from going to the school for a confrontation with Mr. Hamilton. I knew that whatever the outcome of such a meeting, I’d suffer further in the long run. My father finally relented, and I now wonder if the glowing letter of recommendation could be traced to my father’s visiting the red-nosed assistant headmaster just before we left the country and reminding him of the incident with the strap “Very intelligent boy,” indeed.

Finally, though, we were off. Crossing the Atlantic took eight days in occasional heavy weather. My father and I were berthed in one compartment and my mother in another, a separation that violated the terms of our passage and angered my parents for years. For my part, I couldn’t suppress a tinge of disappointment not to be sailing on what I considered the more elegant—and three-funneled—Queen Mary, rather than the blockier-looking and two-funneled Queen Elizabeth. But the voyage in the great floating palace certainly exposed me to eye-opening experiences, including meals more sumptuous in surroundings more luxurious than anything I’d ever imagined.

I was also horribly seasick for two days, partly because our tourist-class compartment was so far belowdecks, which in those days before ships had stabilizers meant the motion of the waves was magnified. Hoping I might die soon was what kept me alive. I suffered in my berth in the cramped compartment for a day or so; then the cabin steward told my father to get me up into fresh air, because the steward had no intention of waiting on me any longer. The fresh air did cure my sickness, but I took perverse satisfaction in throwing up in the elevator on the way up to the top deck. I’ve never been seasick since.

After the fresh air on deck had blown away my mal de mer, I took a much livelier interest in details of the voyage—and the food in the impressive dining hall, which seemed more like a ballroom with its marble columns and staircases. I still have several of the menus bearing pictures of the ship and listing the delicacies that made the trip feel like an enchanted voyage.

Up top, with the vast Atlantic waves stretching away in every direction, I discovered deck tennis, which involves tossing and catching a hard rubber ring across a net. From a distance and through a fence I could see the tiny swimming pool for second-class passengers, but the likes of us in tourist-class had to make do with fresh air and occasional sunshine. I kept looking for icebergs, but never actually laid eyes on one.

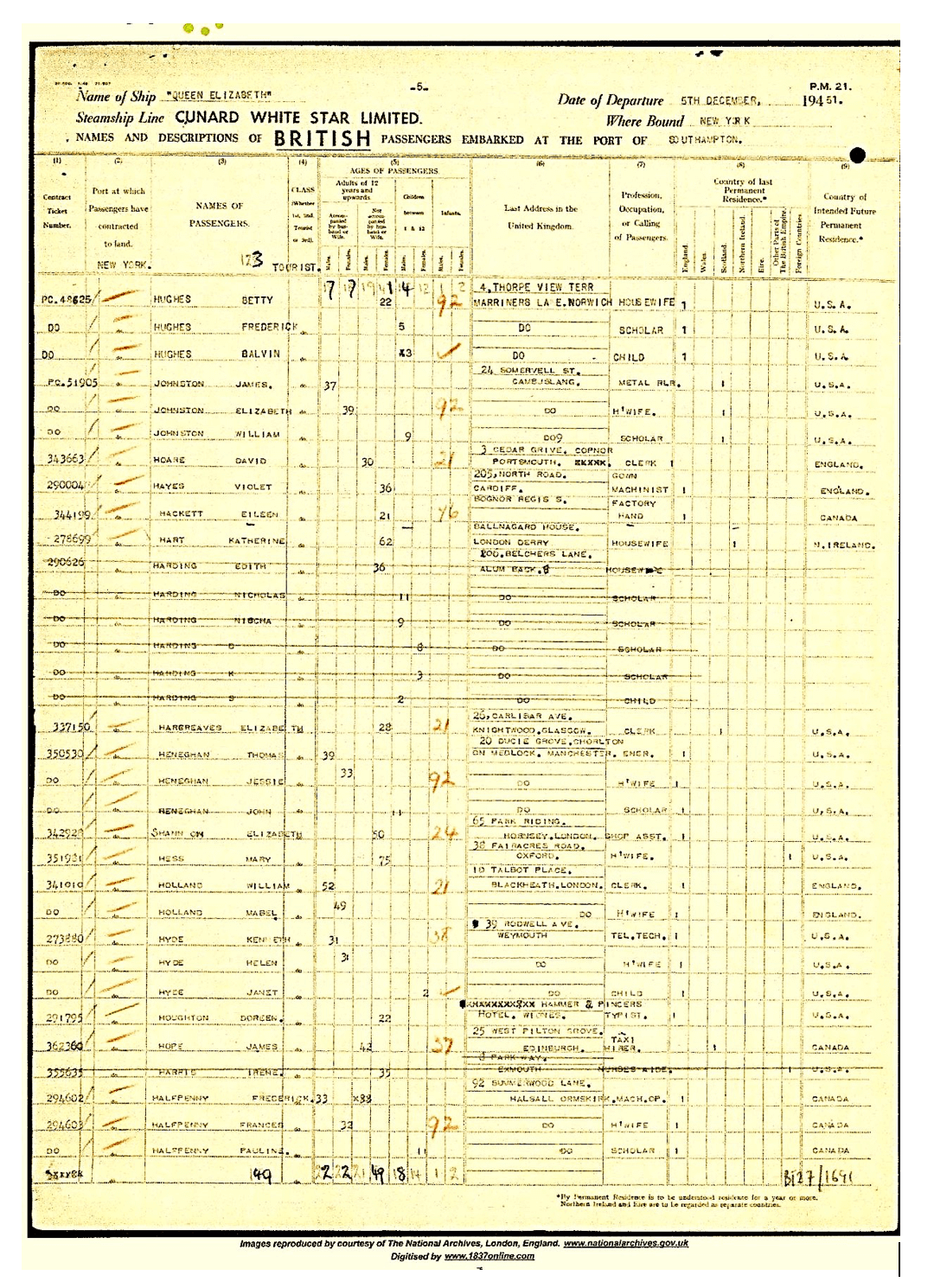

The page from the QE II’s passenger manifest, showing our family’s names near the top and giving my grandparents’ Somervell Street address. My thanks for this to my cousin, Moira Smith.

My parents, especially my father, were obviously much worldlier than I, but I could tell that even they were impressed by the food and the opportunity to enjoy ballroom dancing every night to music by a full orchestra. They also enjoyed the lime rickeys mixed expertly by the always-obliging bartenders. I watched the dancing and drinking and listened to the music most nights, trying to stay out from underfoot and occasionally roaming the passageways and upper deck, careful to avoid the ever-vigilant stewards.

One night while my parents were preoccupied with dancing, I sneaked up on the weather deck and discovered why a rope stretched down the center of the companionway at about armpit height. When I stepped into the open air something made me grab instinctively for the rope, and what felt like a gale-force wind seized me and blew me aft, all the way to the far end of the tourist-class deck. I hauled myself back to the watertight door and quietly made my way below deck to the ballroom.

Arriving in New York we saw the Statue of Liberty, then endured immigration processing—during which an obviously bored INS officer asked me a series of questions in a voice that never rose above a nasal monotone, including the inquiry if I’d ever been a prostitute. Finally escaping the clutches of the INS, we retrieved our luggage. Then a hair-raising taxi ride took us to Grand Central Station, where the man pictured on the Philip Morris billboard blew giant smoke-rings high above the marble floors. Another long train journey followed, though this time I didn’t have to stand. We were finally deposited in Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, every bit as cavernous as Glasgow’s and New York’s.

My Uncle, Mitch greeted us in his Lithuanian-accented English then loaded us into his commodious four-door whitewall tired Chrysler, and drove us through downtown Detroit and out Jefferson Avenue alongside the river past Belle Isle. This was years before the city was carved up and sectioned off by expressways. Finally arrived at Great Aunt Tillie’s small East Side bungalow at 3784 Manistique, we got out of the car, trooped up on the porch, and entered the living room. There stood Aunt Tillie looking much like my grandmother, and speaking like her in a slightly squeakier Irish lilt. She welcomed us with hugs and said to me, “You’re just in time for Auntie Dee.”

And there, across the small room, a tiny and pleasant middle-aged woman was introducing a cadre of singing and dancing moppets not unlike me. I later learned that her name was Dee Parker, formerly a touring singer with Tommy Dorsey’s Orchestra, and now a daytime television hostess on Detroit’s WXYZ-TV. She wasn’t on an enormous triangular screen, but she was undeniably broadcasting all over the part of the planet occupied by Greater Detroit . . . on television. The feeling wasn’t quite like standing in the vibrating bell of sound from the Queen Elizabeth I’s foghorn, but it just as surely signaled a radical change in my life. I’d certainly have to write a letter to Jim Simpson. And maybe even David Dennistoun and Andy Guy, too.

So much for the powerful—and fictional—Emperor Ming. Television had suddenly gone from a fanciful notion to being a part of my daily life, along with many more elements of culture-shock I would encounter in the months to come. Even Ming, Flash Gordon, Dr. Zarkov, Dale Arden, and all the rest could be found on the small screen, along with Soupy Sales, Milky the Twin Pines Clown, Howdy Doody, Captain Video, and Tom Corbett, Space Cadet. But it all began with Auntie Dee.